Gavin McCormack is a trained Montessori teacher, children’s author, teacher trainer, philanthropist and school principal. Initially trained as a mainstream primary school teacher in England, Gavin re-trained as a Montessori teacher in Australia where he found the understanding and experience that has inspired him to build several schools and teacher training centres in the Himalayan regions of Nepal. Gavin has trained teachers, parents and educational leaders across the world. Immersed in the teaching profession for over twenty years, Gavin’s journey has been driven by a passion to understand what it means to truly educate with a genuine intention of bringing out the full potential in those whose lives he touches. This interview tells the story of Gavin’s one-man quest for global education reform and the reasons behind his unexpected decision to leave Farmhouse Montessori School in Sydney’s northern suburbs after four inspiring years as its principal.

INTERVIEW - Gavin McCormack is interviewed by Mark Powell (Montessori Australia)

Mark: Gavin, what’s your Montessori story? How did you find Montessori?

Gavin: Very interesting question! I was working in Rissalah College in Lakemba NSW for about 10 years with refugee children from around the world – at that time especially from Libya, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran – and it was beautiful. I really loved working there! And because they had been through hardship and had these amazing stories to tell I wanted to make sure that those stories were heard. Although it was quite a strictly scheduled school where it was all about exams and grades and points (which I'm not about today) I wanted to make sure that all the children in the class could learn from the children who were arriving from Libya, that their stories could be heard. So I started to individualise the programme to meet every single child’s history, their needs, their backgrounds, and allow them to have a platform to tell their stories.

Now, what happened was we had a random inspection by NESA [the NSW Education Standards Authority] and a lady called Sue Bremna came into my classroom to observe one of my lessons teaching English. At the end of the lesson she said to me “Are you a Montessori teacher?” I said, “No, but I've heard about Montessori. Is it a cult?” She laughed and said “It's not a cult, but I think that you might be a Montessori teacher and you have no idea! I suggest you go and have a look at a Montessori school.” So I went home and did a bit of Googling and thought “Wow, this is pretty cool! I like this!”

Anyway, we had a new principal at the time and he left after a year and went to a Montessori school. He called me about two months after he left and said “Hey, I'm working in a Montessori school. You need to have a look at what is happening here, it’s in-line with everything you do!” I said, “Okay, I'll come and have a look” and I walked into a stage three class at this particular school, and was like, wow!…This is why I say that we can bring Montessori into the mainstream because I was doing that without knowing it for a few years. I had the philosophy but I didn't have any idea about any materials. A job came up at this particular school, I applied and they gave me a job!

In the beginning, I was in the classroom without knowing one piece of material and I felt helpless, so I know how that feels. When you're looking at all these shiny, wonderful objects you wish you could touch them and someone slaps your hand and says, “Don't even think about touching the bead frame, you’re not trained!” and you shrink, “Oh, sorry!”

But yes, that was how I got into it and I since then I haven't looked back. It’s absolutely changed my life! I was just a teacher like anybody else until I got Montessori, and now I'm in a position where I feel like I can shout this and people will listen. Now I’ve got all these schools around the world saying “Please help us, we want Montessori too!” And here we are, having an interview, and that’s amazing for me and I'm very grateful.

Mark: Why do you think Montessori is not more widely adopted in Australia and around the world? In Australia only about half of one percent of schools are Montessori and perhaps triple that for Early Childhood Centres, which isn’t anywhere near enough to bring about Dr Montessori’s agenda for social reform. Only twelve hundredths of one percent of all school-age children in Australia are served by Montessori schools! For a movement with so much potential, after 115 years, there isn’t really any way to sugarcoat that! If Montessori is such a great thing, why isn’t there a Montessori school or centre in every LGA?

Gavin: If you look at the history of Montessori in Australia it started off really well. They were off to great guns, but I think what happened was there was only one stream of training and it was just coming out of one avenue and it as quite strict in the way it was delivered. It can be off-putting. Think about it this way. You've done a degree in teaching over four years at Sydney Uni and you walk out there and someone says, “You want to be a Montessori teacher? Well now there's another three years, maybe four, and it's going to be really really hard with a lot of hours and you’re going to be out of the classroom…”

It's not easy to implement Montessori, there's no question about that, but that's a huge hurdle for many teachers because you want to be in the classroom, learning as you’re teaching. At university they teach you all about the philosophy and classroom management and all about the curriculum and outcomes and assessment…but 99% of it is when you're in the room and it's happening in front of you and you see a child who’s disengaged and you try to figure out what works. I think that’s the big stumbling block.

Montessori wrote a philosophy and a pedagogy and she said this is how you do it and we're still doing it exactly the same way, but the world has changed. Technology is here, there are more people on the planet. Diversity is greater now as countries have grown while the world has shrunk, and we should be able to respond to that. We should have a multitude of training centres and a multitude of integrations of Montessori into our schools, whether you go 100% or you just start somewhere.

The revolution in terms of bringing Montessori into mainstream will happen when we start to allow the Trickle Effect into our schools, where schools and teachers and education executives and leaders can adopt a little bit of Montessori. Once you get a little taste of it there’s no turning back. People are talking about Montessori and they want it, they want this alternative. They want their students to be wonderful, well-rounded people. They want goodness in a student. They’re not looking for grades anymore, points or percentages, they’re looking for education for the whole child and it’s just round the corner.

Mark: So how do we change that reaction that to do Montessori properly you have to do it perfectly, that if you don't hold your little finger in the right way in the the pouring exercises then you're going to ruin the child?

Gavin: She had a point in that getting it right initially is key with children. The old saying is that if you teach something wrong to a child under seven you have to reteach it 65 times until they actually get it. That one window of time when you teach something the first time is the one they will retain, because of the imprint on the brain the first time you put it there. For example, when I was younger my mom said eggs are disgusting, you shouldn’t eat them, and for most of my life I've avoided eggs because it was the first thing I heard about eggs. Actually I love eggs now, but it took me 35 years to like them because it was ingrained in me not to.

So she was right about that. Some of those smaller details are a bit over the top – the finger in the right position when you’re pouring – but in bigger concepts like multiplication, communication, your place in world history for example, things have to be done correctly in a sequence. However, in terms of the Trickle Effect I think that it's very hard to go whole hog straightaway.

If you look at what's happening with Cop 26 in Glasgow right now we’re not asking countries to turn off coal immediately. We're not saying turn off all power stations straight away. The whole world can't go without power! We’re saying make some targets, Trickle Effect, walk it into your country, but by this time we want to make sure that we're using renewables.

It’s same with our schools. I’m saying, you want to be a Montessori school? No problem! Let’s start with the philosophy first. Start with your understanding of the child. What is the child? The child is not an empty vessel to be filled with information from your brain to theirs. We need to change your thinking. Many teachers around the world are still thinking like that – these kids are sitting there slightly empty, I know everything, so I’ll fill you up with information. We don’t need that any more, that time has gone, children can find the information themselves. What they really need is for us to guide them, and hence Montessori teachers call themselves Guides because they guide children in the journey that they want to follow.

The Trickle Effect means that we take it on step by step. First we look at the philosophy, then we left look at the understanding of the child, then we look at what the structure of a lesson looks like and how to scaffold independence, then we look at how a classroom environment can be set up to allow this to flourish. You’re five steps in, maybe that's a six month process, but at that point you don't need any materials training, you don’t need to turn a tile over in a certain way, point your finger in a certain direction, you just need an understanding of the child and your place within the environment, and then we can start to introduce materials.

Learning all these 500 pieces of material, how to deliver them, how a kid will use them, where they go on the shelf and what they mean, all in sequence, all of this can be quite off-putting because it’s a very, very big job! Instead of learning how to bake this very big cake with a very long recipe, let’s learn to cook in bite-size recipes. Let's learn how to use the Geometry materials first. Everybody in the school is going to get a Geometry shelf. This weekend you're all gonna come into school and I'm going to show you how to use every single piece of Geometry material. And the ones I don’t, don’t worry about it, somebody online will teach you those.

I think once teachers get a taste, there's no turning back. When they see their students come in, choose their seat, plan their day, organise their diary, become independent, go to shelf, pick up their material, start working, teachers will think, “Ooh, this is what I’ve always wanted! Actually when can I get my hands on the Language materials? When's that shelf coming?” And you say, “Don’t worry, that’s coming in Term 3. You get your head around the Geometry materials first!”

Mark: And that would certainly match the way the world works now more than it did 100 years ago…

Gavin: There's also this illusion that Montessori avoids technology. But it's mandated! Children need to know how to search, type a spreadsheet, create a PowerPoint presentation, use a mouse, do some coding…this is the future, it’s 2021 and they need to know these things. But it's how those things are implemented which is very important. So it's not about avoiding it, it's about how you make it available. Freedom within limits means you can use the computer but you can only use it for half an hour, and there's a timetable, and you have to schedule it, and when your half an hour is up you say, “I’m so sorry, you have to find an alternative source of information.”

And you see that when you ration these things children start to think, “Okay, if we've only got half an hour on the computer then what's the most important use of this time?” and you hear these amazing conversations between children. We have this wonderful window in the morning from 8:45 to 9:05am. We don’t start class till 9:05am but we open the doors at 8:45am. Kids come in at 8:45 – they’re all here – and you hear these conversations between seven year-olds getting their diaries out to plan their day. Children will say, “Hey, should we do our work on dinosaurs this morning at 9 o’clock?” and Little Tommy says, “Well, actually I've got a lesson this morning on triangles from 9 till 10 with my teacher but I'm available at 10 o’clock, and then Little Sandra says, “Okay, 10 o'clock it is. I'll bring the card, you bring the paper. Do we need the computer?” “I don’t think we do. Let’s just use books today. I’ll book the computer tomorrow, alright?” And they both write in their diary: “Meeting, red table, ten o’clock, dinosaurs, bring paper.”

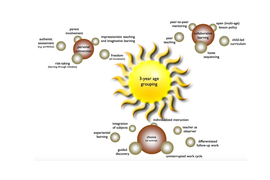

This is executive functioning, this is time management, they’re compromising, they’re understanding each other’s perspective, they’re planning…this is what you see from high-powered executives, but these kids are seven! They’re reading clocks, they're estimating how long they’ll need and what resources? Will I need it today or will I need it tomorrow? They’re predicting the future. They've got an uninterrupted work cycle, however they've got what we call ‘non-negotiables’ so they can't just do Art for six weeks all day everyday because there are also times they’re going to have to come to lessons and they need to make sure that they’re there. For the rest of the time they’re totally free, they just have to come for this or that. It’s a really nice balance between what's required and what's free time.

These are all things that we miss out on when we say, “Okay everybody, it's now 9 o’clock so it’s Literacy. Open your book, let’s all read the assignment as I'm writing on the board. We’re all doing the same thing…Now it’s 10 o’clock, close your books. Let’s all do mathematics. You take away that responsibility from our students and we underestimate the capabilities they have. They can do it, we just need to let them try!

Mark: So you've been a principal for four years after teaching for quite awhile. What expectations did you have upon the taking that role and how was reality different?

Gavin: Okay, so I was class teacher for a long time and I was nervous about going into a principal’s role, I must admit. You know it's easy to make children happy. I’m not trying to brag but I found I have this gift with children. We just get on really well and you know we trust each other and I love every minute I'm doing that!

Then suddenly I was managing teachers and managing parents, managing the Department of Education, and that was a bit daunting and actually I didn't know what I was doing, I must be honest with you. I tell the children “Just start, it doesn't matter, if you fail it’s all good, you'll learn along the way.” So I thought, you know, I should practise what I preach. So let’s go for this and see!

Luckily I had my PA, my dear friend and colleague Suzanne, whom I work alongside. I sat down with her the first week, and I said, “Look Suzanne, actually I don't know what I'm doing. You know I'm just a teacher. I only know how to teach. Can you help me?” She said, “Let’s sit down and go through it all.” She made this beautiful calendar with, like, this is when the funding has to happen and this is where the census goes in and this is the password. The first year we spent a lot of time together and I learnt a lot from her, and we became dear friends.

I think the tricky part of being a principal is all the paperwork! It’s not easy, there’s a lot of responsibility on your shoulders because if anything goes wrong in the preschool, in the primary school, that swimming excursion, sports carnival, you haven't got your medical certificates up-to-date and one child has an anaphylactic shock…which happened to me actually!

There are so many things that can go wrong in front of you. You’ve got all these variables sitting there: parents, community, safety procedures, child protection, there's a lot to keep a track of. But…all of that bureaucracy and stress is outweighed by the fact that you have a community in front of you of hundreds of people who, if you can promote Montessori and change-making and global vision, if you can get your community to come on the journey with you, the impact you can have on the children who sit in your school is huge!

As you know I’ve built new schools in the Himalayas – and my community have helped a great deal. They’ve rallied, they bought materials, clothes, shoes, books, they’ve donated money, some of them have chipped in thousands of dollars to help build schools in the Himalayas. And now I have children who know their value in terms of the impact they can have in the world! I’ve got students right now, today, as we speak, who are running their own charity, planning a garage sale tomorrow in the playground where they're going to be selling household items, and they’re ten years old, raising money so that they can put vanity packs together for women who have suffered domestic violence during lock down living in a local refuge.

These girls, I think to myself, you know your worth, you know your value, you know your power, and you're 10 years old. When you're 16 you're going to be amazing and when you're 30 and you're the CEO of a bank or you're in charge of a military organisation or you’re a local member of parliament, you're going to make your own decisions. You’re not going to pollute waterways, you’re not going to persecute indigenous people because there's sitting on gold or oil or gas, you’ll do the right thing. I sleep well at night knowing that they're going to be the leaders of tomorrow because that's what we're here for. We’re not here for grades – who cares if you get a grade A, it doesn’t really matter. What really matters is going out into the world and being an amazing person, and I’m very fortunate to have had a community who feel the same way that I do and children who are going out there to do these wonderful things. That’s what’s beautiful about this job!

Mark: It sounds like those moments with children, watching that growth happen, those are the unforgettable moments for you as a principal.

Gavin: Look, I see education as all about trust. I go on about this a lot and it comes from the top down. The government needs to trust the principals, that we know how to run our schools. And similarly, principals need to trust their teachers that they can teach, because they’re professionals. You don't go to a surgeon just before they’re about to operate on you and say, “Do you know what you're doing? Do you know how to make an incision? You just trust that they’re professionals. Teachers are also professionals – teaching is a profession! So principals need to trust teachers, and similarly parents need to trust teachers to do their job and know what they’re doing. It’s not that easy to become a school teacher.

But then comes the next level where teachers trust their students. They say, “If you want to build a model of a volcano, if you think that's the best way to represent your research, I trust you. You’ve got this, go and build a model!” Now the model might be rubbish and fall down – they might get the wrong consistency of glue mixed with water and it doesn't work, the paper maché collapses and the student sees it's not worked and is a disaster. Well that's fine, you ask what are you gonna do next next time? He says he’s going to put more glue in. So you say that’s wonderful, let’s go again, let's do this again.

When we promote that trust from the top all the way down to the bottom we get experimentation, and from experimentation we get innovation, and isn’t that what we want in education? We want innovation, but we won’t get that unless we change the way that trust works from the top down. Because, you know, everyone’s micromanaging everyone else. The government says you’ll teach this, say these words. Here is a programme, you can say those actual words and the principal goes, “Oh my God, the government is going to come and check me, that my teachers are doing the right thing. So the principal says to his teachers, “Here is a programme, you better say those words, and I better see it in their books.” And then the teacher says, “Right children, now I’m going to say this and you're going to write it down.” Because I’ve got to report back to the principal and the principal’s got to report back to the government…and it’s all top down and then you get nothing that’s real or meaningful! You just get a lot of dictation from the top down.

If we start from the top and we have an element of trust, and we allow teachers to come and bring their passion into the classroom and their own skills, you’ll see education turn on its head. I've decided that that's going to be my life’s goal. I’ve actually resigned from my job here because I want to be a spearhead of that revolution.

I'll give you an example. I was working alongside a teacher in my school who was previously a restauranteur. He's built some of the best restaurants in the city. Because he’s a chef and a restauranteur he brings this whole new level of understanding to influence education in our school, that only he could bring. I’m not going to tell him how to teach step by step, why would i? – You see, It says in the manual, you will teach it this way, you'll use this chart, use this timeline for example. I think those resources are amazing, but if there's another way or you want to add to that with something that's a passion of your own, then why wouldn't you? Because when you bring passion into the room children can sense that passion and they're automatically inspired. So he was teaching the evolution of man and he wanted to show children how fish emerged from the ocean to land. It’s clearly prescribed in the Montessori manuals and albums how you would do that.

But what he decided to do was to bring a fish in, a whole rainbow trout, and he had it on the table covered with a damp table cloth, and four or five kids in front of him. He said, today we're going to talk about the evolution of man, but we're going to focus on how fish emerged onto land. He said, I want to start by telling you that your great great great great great great great grandfather was a fish.

All the kids started laughing in this little group. They were giggling, and they were like, “That’s not true, my great grandfather was not a fish.” But he goes, “Let me just teach this to you first so you can see what I mean. So he had X-rays of a hand and they looked at the phalanges and saw the structure of it. And he told a story from the Timeline of Life about how fish emerged onto land. The children had some understanding but were still doubtful. So then he revealed this huge trout, and the kids were like, “Whoa, there’s a trout under there!”

He told them to touch it, feel it, and they all touched it. They touched the scales, the eyeball, they opened the fins and immediately all their senses were alive. They could smell it, they’d never touched a fish’s eyeball before. When you ignite a child’s senses they don't forget that and it doesn't go away!

And then he shone a torch through the fin of the fish and you saw the penny drop in every child's eye. They put two and two together and thought, my God, it’s the same as my hands! It’s phalanges are exactly the same as mine! And he said you know your great grandfather’s feet were…and he opened the fins at the bottom of the fish, and they could see straight away that you’d evolved from there, that you’d come from that. Parts of that fish remained in you and the journey was there to see!

Now, if I have told him you will teach from that manual and you will use that chart only, because this is what Dr Montessori said, then that lesson would have been nowhere near as good as it was. It was absolutely one of the best lessons I have ever witnessed in my life! Every teacher has a passion, every teacher has a hobby, every teacher has something they love, and if we let them bring that into school in some capacity when they want to – within limitations of course – then we'll see magic! And that's what I saw that day.

Mark: What are some of the most challenging things you’ve had to do as a principal?

Gavin: The most challenging thing which keeps me up at night is knowing full well that if one of my teachers says “Can I have 5 minutes, Gavin?” in my office – that I dread they say they’re leaving, because I know I'm going to find it very hard to find a replacement. That's why it's somewhat easier to run a mainstream school, because there are hundreds or thousands of really good mainstream teachers out there, and there are no – there are no – Montessori teachers that you can find anywhere!

I’m lucky that I have a board who agreed to have a structure in place so that I always have a backup. So for example in my Stage 2 class I have three teachers in that room: one trained, two in training. That's a lot of teachers in one room for 30 kids! They said “Why, why do you need that?” It’s because if I have a teacher say they're leaving I need someone who can step in, someone who’s in the school, we all trust, we all know, a good teacher who could fill the void immediately. That’s a bandaid solution but it solves the problem very quickly.

You know when I was in England working as a teacher I had an assistant and my assistant was in training to be a teacher. There was this government initiative where if she did four years as my assistant, and she did a few assignments along the way, after four years they’d give her a stamp and she was a teacher.

If we can have that in our schools too, where your assistant is in training – and that training can come from the teacher, because your assistant is 24 hours a day sitting alongside the teacher watching them deliver the materials, watching over the classroom, watching them manage the children, watching them write the programmes, and in some cases the assistant delivers some of that curriculum – then after a certain amount of time, with a couple of hoops to jump through, a little training – not too rigorous – we should say, you know what, you've got the stamp of approval, you’ve done this many years, you are whatever you want to call that, we’ll call you a Montessori hybrid teacher or whatever it's going to be called.

We need a mechanism that’s going to allow us to have more Montessori trained teachers in the system. There's got to be a solution sitting there – we just need to be more flexible.

Mark: So what advice would you have for young principals?

Gavin: Being a principal of a school is about making sure that everybody underneath you works alongside you in your school and that your main objective is to get them to where they want to be. Having a staff meeting isn’t like having a circle with a load of 10 year olds! I’d been in lots of staff meetings before and I was usually really bored. So I asked myself, how do I run one that's not going to be like that?

So the first thing I said was, “In my time here at the school I hope that I can get you to where you want to be, whatever your dreams, whether it’s to be an executive, a coordinator, if you want to leave the school and do something amazing, open your own school…then go for it. I’ll help you get there.” And I say that to my students too.

And third, I want the community to realise the power of working together collectively. If you go in with those three pointers in your mind then you're always going to succeed.

The other piece of advice I’d give is not to beat yourself up too much. You can't do everything right all the time. You can't answer every email when they come in. You have to have a window of time when you say “This is for me.” Because being a principal is 24 hours a day. Parents will email you at 11 o’clock at night!

Mark: How do you manage that work-play balance, that work-life balance?

Gavin: I use a Gantt chart for myself. So I say, alright, if it’s 5:30 at night, everything is off. I don't care what's happening, unless the school is burning down, I'm not going to do anything that can wait until tomorrow morning. I gotta say, at the very beginning I was trying to be everything to everyone, replying to everyone, giving out my phone number, send me a text, no problem, call me! I thought, God, this is gonna kill me if I continue like this.

So make sure you’ve got windows of time for yourself too, because if you don't water your own garden you're never going to see the fruits of your labour. The burnout rate with principals is very, very high so you have to be realistic about what you can actually manage, otherwise you end up being very tired very quickly!

Mark: What are your next steps? You touched a little on that, but can you be more specific?

Gavin: I can. In the holidays over last five years I've built schools in the Himalayas. People might criticise me for this – in fact I've already been publicly criticised, and that’s fine – but there were no Montessori training centres in Nepal. There was nothing, one didn't exist. So I built two, one in Katmandu and one in Butwal on the Indian border. And now they’re the two biggest training centres in the region, pumping out hundreds and hundreds of teachers a year.

Now, you might also criticise me for this – and I'm completely fine with that, my shoulders are broad – our training is three months, that's it, three months long! Now you might think, wow, that's not enough time! But it is enough time to get enough of the Montessori philosophy into schools to make a change. And we’ve seen over the five years I’ve been doing that work, we've seen hundreds of Montessori schools spring up around Nepal. In fact, there are hundreds now, which is brilliant as those teachers have gone on to open their own centres and then reach out to the world for guidance and help, and other Montessori schools are helping. It’s beautiful, and I love that work, I love that work, and the impact of that work for me personally.

I had a conversation with myself in June. I sat down and thought, “Okay, you're 43, what are you going to do with yourself? Are you going to stay at this school forever? You could do this, it's fine, it'll pay the mortgage and you can have fun, the kids are lovely and the parents…

But what would I do if money was no object? If I didn't have to earn a salary, what would I do with my time? Know what I’d do? I’d train teachers for free, I’d build schools for free, I’d take the training to Nepal and Bangladesh and India for free. I’d do it all for free! So I thought, that’s what I’m going to do and I resigned my job! I thought, I’ll find a way, it will come.

I’m going to work with my good friend Riachard Mills and try to provide free education for the world. We have built a site called upschool.com. It’s very cool! I had a little trial of this in September. I did a week called World Education Empathy Week, and you obviously helped me with that. It proved to me that it is possible, that we have the technology now to provide free education to the planet. I'm not talking about recorded videos that sit on YouTube. I'm talking about teachers that wake up like sunflowers as the sun rises across the world. They follow the timezones across the planet, and as the sun comes up the teachers awaken, they go online and say, “Hello, it’s Barbara here. Welcome to Phonics with Barbara! And anybody who can't get to school in that timezone clicks a link and boom, Barbara’s there!

I know technology is a big no no in some parts of the Montessori world, but if I’ve got 50,000 children on the other side of the screen and I’m teaching phonics, that’s easy! But those 50,000 children have all got me, one on one! That’s what's beautiful about this – to them it's one on one! Right now there's two of you on my screen but if you want to Spotlight me then you’ve only got me. I could teach you anything and you’ve got me one on one.

In today's world we can pull that off and there's a lot of children around the world who can't get to school for a multitude of reasons, whether you're a girl in Afghanistan who is not allowed to go to school, or you’re in an abusive household and your father's not letting you leave, or you’ve got an alcoholic mother, global disasters, tornadoes, whatever the situation might be – there are a multitude of reasons why people can't get to school. But the Internet is about to be everywhere in the world, and we can have a platform where it doesn't matter your socioeconomic background or whatever hardship you're facing, click here and Barbara is there! “Hi everyone, it’s Barbara for Phonics!” And Barbara is there every week so you can build that relationship with her.

I did the mathematics. You need 450 teachers to teach the world! That’s it, from K to 6! Just 450 teachers giving two hours a week to teach the entire planet! You just need the technology, so we're going to do it! We’re not going to give up until it’s done!

So I'm going to put my energy into philanthropy and do that kind of work, and I don't really care about money. I don't have any but money will come. That’s what happens.

Mark: Wow! What an inspiring interview! Thank you, I can’t top that so we’ll have to leave it there!

Gavin: I will say this last thing, that Montessori has been around a long time in Australia. Montessori teachers are wonderful and the community is fantastic, but we have to be open and we have to be really flexible in the way that we operate otherwise we risk the chance of this thing dying and we don't want that to happen.

A very famous quote that I live by is that the only constant in education is change, and you’re that change. That’s the truth! If we don't change, then we end up falling by the wayside and we don't want that. Montessori is too good for that.

[Edited and Abridged by Mark Powell]